Apr 5, 2019

Aerial Photography Among Alaska’s High Peaks

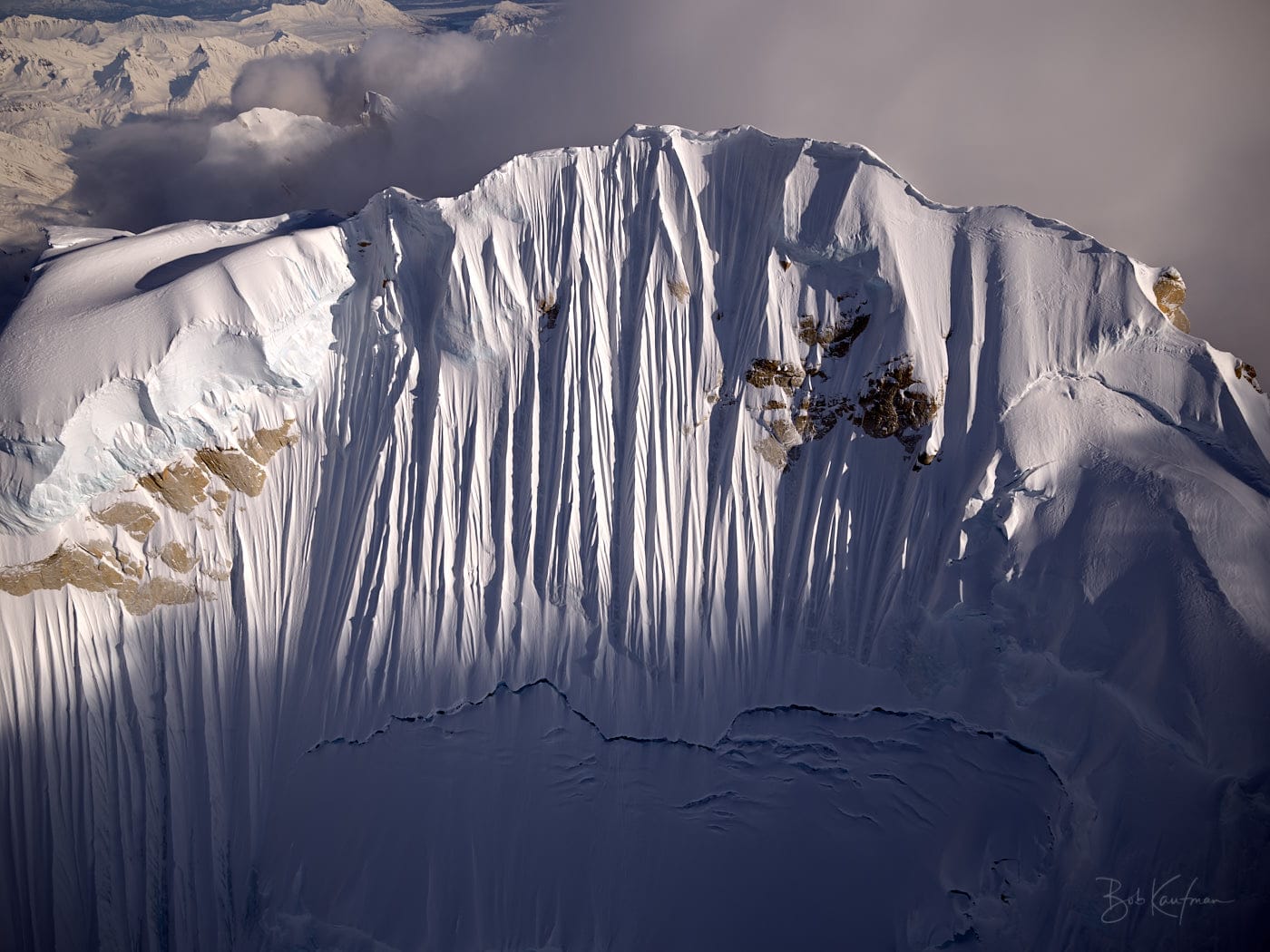

I set off from Anchorage on a fine early Spring afternoon hoping to capture the mile-high granite walls of the Ruth Glacier in golden evening light. Even better would be to get them in “lingerie effect”—shapely mountains scantily visible through wispy clouds.

We flew an hour and a quarter to the Alaska Range only to discover the conditions were more like a “kimono effect.” Heavy cloud cover above produced flat light in the Ruth. Mother Nature did not seem inclined to lift her kimono even so much as to give us a glance of what we were hoping for.

So what do you do when the lady plays hard to get? You play by her rules. We climbed to 8000 – 9000 feet, where the peaks were somewhat less obscured.

Limited visibility still made it tough to find simple, dramatic compositions. Exposure was also challenging: bright background sun shone through heavy clouds while foreground walls remained in deep shade.

She then handed us an unexpected gift: updrafts that carried us up to 13,000 and even 14,000 feet—the service ceiling of the helicopter. I had never flown the R44 that high before.

At those altitudes, you are flying a machine with severely reduced performance characteristics. The engine is not producing much power. The blades are not producing much lift. And cyclic, collective, and foot pedal control inputs give you very little authority. In the nearby video, I talk more about how we manage the risks and divide the workflow requirements of photographing in these conditions.

You need by-the-book piloting skills—but with them, you are not only just fine, but able to explore the wonders of a world of rock and ice that lies miles above any signs of life. Floating among the highest peaks in North America almost three miles into earth’s atmosphere with the door off the helicopter is an experience that makes you feel at one with Creation. You are able to study details, like circles of lichen on an unclimbed rock face, or overhanging cornices that you can reasonably believe no other human has ever seen, at least up close.

For me, chasing art in an extreme environment like this brings back the kind of unbridled excitement I felt often in childhood. The more adult side of me (if there is such a thing) was mildly disappointed that we burned a total of 5¼ hours of fuel and didn’t really get what I was hoping for. It doesn’t always work out, but I’m still pleased with some of the images I got.

In another post, I discuss how I think about subjects and framing when photographing big walls. By no means do I have this down, and I would appreciate ideas and suggestions from other photographers and artists.

Technical Details

Camera, Lenses & Shutter Speeds

I shoot with a Phase One IQ3 100MP Trichromatic back. I shoot 1/250th or faster with my 35mm lens (Schneider Kreuznach LS 35mm f/3.5) and 1/320th or faster with my 55mm (Schneider Kreuznach LS 55mm f/2.8 lens). Schneider lenses are among the few in the world that can resolve the 100 megapixel Phase One images.

ISO Settings

For distant subjects, I set the f-stop to 5.6 and let the ISO float. It seldom rises above 200 during daytime, even under heavy clouds due to the reflectivity of the snow and glaciers. Just after sunset, it will rise to 800 or even 1000 for a snowbound scene. I have found these settings to be tack sharp edge to edge.

F-Stop

When flying at 12mph (minimum safe speed at altitude) within 50-100 feet of moving foreground elements, I up the shutter a stop and the f-stop to at least to 7.1 for more depth of field. I should perhaps test shooting at f11 and the preset hyperfocal point for even more depth of field. But I try to avoid too high of an ISO, because my professional goal is to sell large fine art prints—and I don’t want to get too far away from 35 ISO, the native ISO for the camera.

Long Lenses

I seldom use my 105mm for aerials, both because I can easily bring the subject in by flying closer to it, and also because it magnifies the camera shake to the point where I would need to increase the shutter speed to 1/1000th or more.

Capture Control Setup

The rear button on the camera is set to autofocus. The shutter half press button is disabled because of the fast-moving environment I’m working in. The Capture Pilot app displays to an iPad mounted in the cockpit, so 1) I can review what I am getting and 2) my co-pilot can better understand the framing I am trying to achieve. I periodically double tap on an image to zoom to 100% and make sure everything is sharp.

Software

I process my images solely with Capture One software. Generally, I let the software auto adjust Exposure, Contrast & Brightness, High Dynamic Range, and Levels, then I work from there. The Linear Response curve (under “Base Characteristics”) works well for high contrast scenes.

No Gyros

Our film and video production company owns several Kenyon handheld gyros. But they are not necessary for still images. Fast shutter speeds do the trick. With the 35mm lens, I’m already holding almost 8 pounds of camera out the open door of a helicopter, and I’d prefer not to increase that further.