Alaska Then & Now

Alaska Then & Now Book

In the late 1990’s, while visiting my parents in Colorado, I noticed a brand new coffee table on the dining room table, “Then and Now: Colorado 1870-2000.” A Colorado photographer named John Fielder had obtained 30,000 prints from the 1800’s and rephotographed 150 of them to reveal the changes that had occurred in the Colorado landscape over the course of a century.

I almost kicked myself when I saw it. It was so similar to what I had tried to do years earlier in the Arctic! John’s book was such a work of art that, even at the hefty price of $85, it became Colorado’s best-selling regional title of all time.

Some of his images were of wilderness. But many were acquired from road-accessible locations. It dawned on me that I might be able to produce a similar book for Alaska if I hewed more closely to populated areas.

I tracked down John through the Colorado Historical Society. We ended up having many conversations. He believed an Alaska Then & Now book held great promise and gave me the encouragement I needed.

Through months of research online and digging through the physical archives at the Museum, University, and elsewhere, I amassed and organized a library of over 1000 historical photos that begged to be rephotographed. (Here’s a small selection).

The stories they told fascinated me. I saw scenes of early Anchorage, almost unrecognizable today due to development. I also discovered once-bustling towns, like Katalla or Curry or Artic City (sic) that had long since vanished into remote wilderness.

I approached cruiselines, The Alaska Railroad, and other major Alaska companies about sponsoring the project. None bit. So I took it on as a personal passion project which lasted for several years. In all, I produced two dozen pairs, all within a couple of hours of Anchorage.

Rephotography gives you knowledge about the past that few others have. I learned this on my first outing, just south of Anchorage.

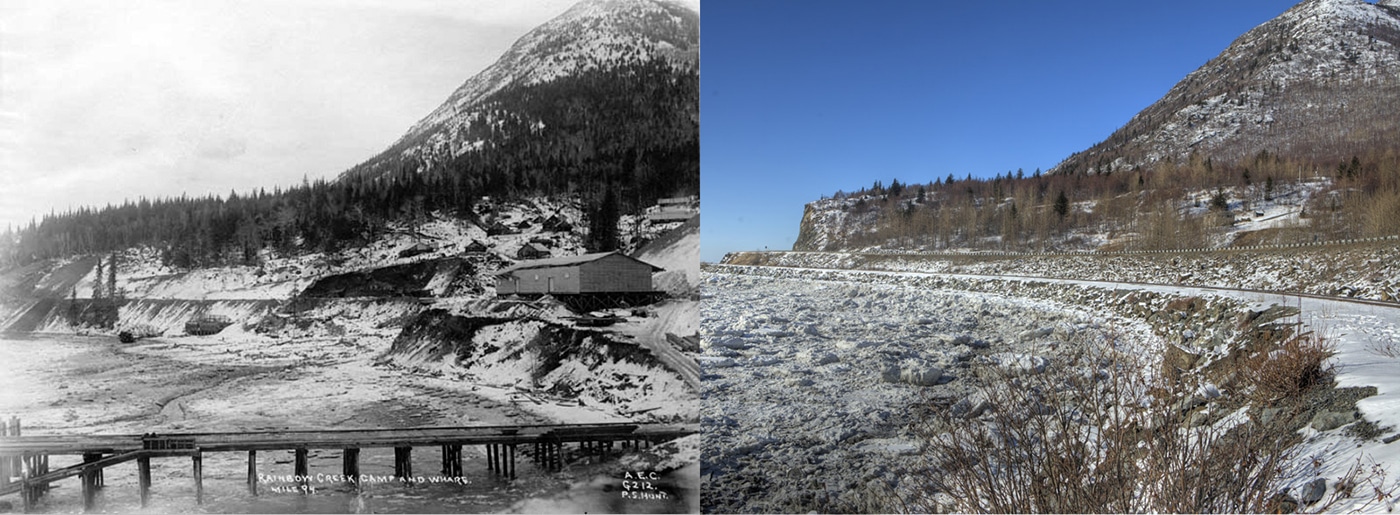

In 1917, in anticipation of building a railroad, the Alaska Engineering Commission documented the entire route from Anchorage to Seward. One picture from that collection, “Rainbow Creek Camp and Wharf,” shows a long wooden pier jutting into the Inlet.

Though I know I was in the right spot, I could find a trace of it. And no one I asked could tell me anything about it! In the same image, you can see a thick forest high on the hillsides where none exists today, suggesting that at some point it was either logged or wiped out by an avalanche. Another striking realization from this collection is that snowprints on the mountains across Turnagain Arm follow an identical pattern 100 years later.

Tracking down the location of a historical photo is like being on a detective mission. Over time, I became proficient at lining up the intersections of foreground and background ridgelines to pinpoint the exact spot where the original was taken. I feel such a strong sense of connection to the past when I know my tripod legs are standing in the very spot the historical photographer used.

It‘s also exciting when I find large rocks that have weathered only slightly through the years or a thin sapling in the “then” photo which is now a fully-grown tree.

Unmatchables

I also found that some photos can never be recreated. I call these the “Unmatchables”:

- Shorelines and escarpments blasted away to make room for roads and railroads;

- Camera views now blocked by buildings, vegetation, or even shifting terrain;

- Towns sunken into the ocean due to earthquakes;

- Ghost towns vanished into the forest without a trace.

On a trip together into Prince William Sound in 2008, a research geologist for the USGS named Bruce Molnia told me about fascinating unmatchable cases he has encountered. (Bruce has likely visited more Alaska glaciers than anyone alive. He uses rephotography to document their drastic retreat. You can see his then-and-now pairs on Alaska.org.)

One is “isostatic rebound”. As glaciers in Southeast Alaska retreat, they take weight off the earth’s crust. In places, the surface has sprung back up 10 feet or more. No one will ever again get the vantage point where the original photographer placed his tripod.

(Bruce told me other interesting facts about isostatic rebound. John Muir’s shoreline cabin in Glacier Bay is now 150 feet into the woods. And in Gustavus, the most rapidly isostatically-rising surface on the earth, 1920’s shoreline homesteads now rest a mile inland, giving rise to interesting legal issues of land ownership.)

Another is tectonic changes. In photographing Chenega Glacier, Bruce discovered that the 1964 Earthquake caused differential tilting of the bedrock in the valley so severe it now obstructs the view of the glacier in the distance.

Bruce also helped me understand a conundrum I was experiencing. In some cases, I was certain I had found the right spot. Yet the mountains would not line up with the original. Bruce explained that some old cameras had rotating lenses. Unlike today’s frame camera that captures the entire scene simultaneously, unequal rotation speed could compress or stretch landscape features in the interior of the frame!

Resources/Links

I highly recommend repeat photography to anyone interested. You will learn a lot and never see the place the same again. Here are some resources to get you started:

- Alaska Images I Curated: I selected these as great candidates to repeat photograph in Alaska. [I’ll have to upload them first in order to link to them.]

- Vilda: Search a vast collection of Alaska digital archives, from which many of mine came;

- University of Washington: Search multiple collections that include Alaska;

- Library of Congress: Includes a small Alaska collection;

- National Park Service Repeat Photography Project: Documents changes in Glacier National Park, Montana;

- Repeat Photography of Alaskan Glaciers: Documents changes in Southeast and Southcentral Alaska.

Let me know if you fall in love with this. Maybe we can work together to produce a quality “Alaska Then & Now” Book.